continued from Part 3a - Granada's Albaycin and Old Town

See maps in that part to understand locations mentioned here

See maps in that part to understand locations mentioned here

Reminder: click on any picture to enlarge it

If something interests you, follow links for additional information

A Brief History of a First Rate Place

"The Ornament of the World" by María Rosa Menocal summarizes the history of Moorish Spain on its pages 15-49 in a chapter called "A Brief History of a First Rate Place".

A 2-hour PBS TV program based on the book is available for those who

have PBS Passport, and short clips from it are available for others here.

have PBS Passport, and short clips from it are available for others here.

Each of the individual periods that ebbed and flowed lasted for more than the 254 years that the US has existed as a nation.

After Rome fell to the Visigoths in 410, the Visigoths ruled and procreated in Iberia for 3 centuries. Under their rule Roman civilization in Iberia collapsed; Iberia languished and fell into disarray.

In 711 Abd al-Rahman arrived in Spain's Al-Andalus from the Arabic world. The Moorish culture spread, intermingled, and flourished throughout most of Iberia for 300 years, centered in Cordoba.

During the period from 1009 to 1031 Cordoba gradually collapsed and fragmented under the pressure of Christians from the north and internal Muslim civil war.

During that turbulent period various cities became independent, including Granada. The Zirid dynasty was founded in 1013 in Granada which began the period in which the Alcazaba Cadima and the Zirid Walls in the Albaycín blossomed and then faded.

In 1212 the disunited Christian factions in northern Spain united, and with help from other European armies began to overwhelm the Moors. Cordoba fell in 1236, Seville in 1248.

As a reward for siding with King Ferdinand III of Castille in the battle for Cordoba in 1236, Ferdinand III granted Granada's Ibn Ahmar some autonomy, starting the Nasrid dynasty.

During the next 256 years Granada, the last toe-hold of Islam in Spain, blossomed -- the city expanded (the Nasrid walls were built to protect it), and The Alhambra was built, the last, late blossom of the Moorish culture in Spain. Finally, in 1492 Boabdil was forced to hand its keys to the Catolic Kings, Ferdinand V and Queen Isabella, and embark on his exile.

During the next 256 years Granada, the last toe-hold of Islam in Spain, blossomed -- the city expanded (the Nasrid walls were built to protect it), and The Alhambra was built, the last, late blossom of the Moorish culture in Spain. Finally, in 1492 Boabdil was forced to hand its keys to the Catolic Kings, Ferdinand V and Queen Isabella, and embark on his exile.

|

| The Alhambra as seen from the Casa de Castril - The Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology of Granada |

"Such is the Alhambra—a Moslem pile in the midst of a Christian land, an Oriental palace amidst the Gothic edifices of the West, an elegant memento of a brave, intelligent, and graceful people who conquered, ruled and passed away."

- Washington Irving as quoted by Cullen Murphy in his article "Tales of the Alhambra - The lost Islamic world of Southern Spain—and its modern echoes" in The Atlantic, September 2001

I wish I had read that article in The Atlantic before our trip. It encapsulated our experience in Granada and later, in Cordoba and would have prompted me to read more in preparation of our trip.

Washington Irving

After breakfast, we walked along the Darro River to the Plaza Nueva, thence along Cuesta de Gomérez, past the Puerta de las Granadas, up the hill to The Alhambra's Justice Gate (Puerta de las Juctica) . (From the plaza it was only a little over a kilometre with an elevation gain of about 87 meters = 320 ft..)

|

| Puerta de las Granadas |

But this time, sadly, he wasn't friendly to us. He was as cold as bronze.

Washington Irving became enchanted with the Alhambra when he visited and possibly camped in it with a friend during 1828, - a story well-told here. His collection Tales of the Alhambra was instrumental in imparting (in his words) "the witching charms of the place to the imagination of the reader" and, I might, to the imagination of future generations.

During his time in Spain, he also wrote A Chronicle of the Conquest of Granada. Both of those books are now online thanks to The Project Gutenberg.

His well-read writings popularized a fascination about Moorish Spain and seeded an interest in The Alhambra, which led to increasing tourism to it increasing conservation efforts for it.

The Alhambra

There are many websites about the Alhambra, its tickets, photographs, and history. I've linked to some of them at various points in this blog. But the one official website, especially for tickets, is https://alhambra-patronato.es/en/. Most (not all) of the following links are to its various pages.

When planning the trip we had been a bit confused by the descriptions of tickets needed. The confusion was resolved when we walked through the Justice Gate: we could just walk in - no tickets needed. Much of the Alhambra was free,. But you did need a ticket to visit three of the most popular well-known areas. We had bought tickets online directly from alhambra-patronato with entrance to the Nasrid palace scheduled for 11:30. That gave us plenty of time to explore both before and after.

|

| The Justice Gate |

Map of the Alhambra and Generalife

|

| Map from the LoveGranada website here |

For a more detailed map (with north in the opposite direction from the map above) click here

For an overview description of the Alhambra by the Alhambra's website click here.

For an overview description of the Alhambra by the Alhambra's website click here.

The Alcazaba

The Alcazaba, the heavily fortified military complex at the point of The Alhambra, stands guard over it and all of Granada. The Alhambra's fortifications seemed impregnable. The Alcazaba (and the Alhambra) were never overcome by force. A long siege forced the surrender.

|

| As Granada grew it needed more area enclosed by walls, hence in the 14th century the Nasrid Wall was built. |

|

| Albaycin (with the 11th Century Zirid city center (the Alcazaba Cadima) on the the left skyline - look for the white tower with Sacromonte center rear and the Darro Valley extending to the right |

|

| Albaycin (with the 11th Century Zirid Alcazaba Cadima, on the the center right skyline - look for the white tower) with Sacromonte far right and the old town extending to the left. |

The Nasrid Palace

Even with pre-bought tickets preassigned in 30 minute increments, the line to get into The Nasrid Palace was long. The ticket managers were strict. We misjudged the line and got to the ticket manager while they were admitting those with tickets for the slot before ours; we had to go sit next to a wall with others until our time slot, then had to guess what location in the line to squeeze into for admittance during our time slot.

There is so much to experience at the Nasrid Palace; we'll pause at just a few key rooms.

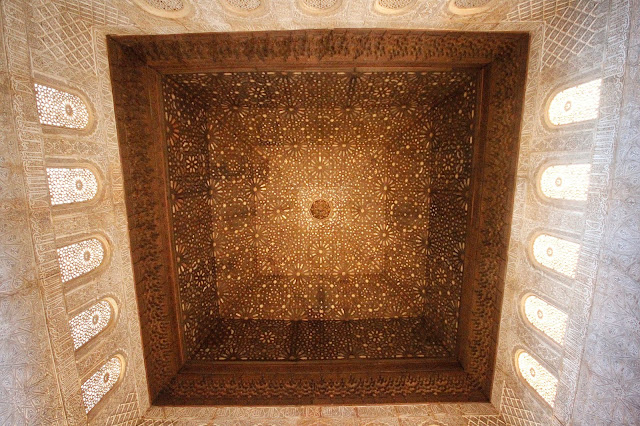

Grand Hall of the Ambassadors

The Comares Palace was the official residence of the Sultan. Perhaps it isn't happenstance that its tower is the highest in the Alhambra. The Grand Hall of the Ambassadors was the throne room in which the sultan received dignitaries and supplicants.

It's size, the largest room in the palace, bespeaks its ceremonial uses. Its ceiling bespeaks its importance and the power of the Sultan. I could not get a good photo of it, so retrieved one from Wikimedia Commons.

It's walls are totally covered in sculpted designs and sacred quotations.

|

| Ceiling of the Hall of the Ambassadors - Photo © by José Luiz Bernardes Ribeirofrom Wikimedia Commons licensed under the Creative Commons - Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 license |

Courtyard of the Myrtles (Patio de los Arraynes)

The Courtyard of the Myrtles, like many Spanish patios, was central to everyday life in the the Comares Palace. Behind it stands the Comares Tower containing the Grand Hall of the Ambassadors.

A photo of the state of the courtyard in the late 1800's is contained in a photo album of England's Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII), here.

|

| Courtyard of the Myrtles (Patio de los Arraynes) |

Courtyard of the Lions

The overwhelming importance of water to the Alhambra can not be overstated. An essay about water and the Alhambra is here. Of all the links that I reference, that is the one I most encourage you to read.

As the website of the Alhambra states: "On a small scale, the Fountain of the Lions represents the entire technical concept behind the creation of the Alhambra, a structural conception rooted in human and constructive experiences developed creatively over many centuries."

The fountain was so important to the rulers (it served their own house) that it was fed by a separate water system than that for the rest of the Alhambra and Generalife.

I think I remember reading somewhere that at some time after the 1494 conquest the fountain and lions were in part disassembled in an unsuccessful attempt to figure out how the fountain worked. It was not until a major restoration between 2007 and 2010 that how it works was rediscovered and it was made to work again. (But I can't find that reference, so I'm not sure if its true.)

That 2007-2010 restoration won a European Heritage award.

Hall of the Abencerrajes

This is one of the more notorious rooms. But more importantly, it presents a chance to investigate the Mocárabe seen in so many of the Islamic spaces.

It's notorious because of one of the legends (or a rendition here) that Sultan Moulay Hacén (father of Boabdil) invited 30 or more guests of the Abencerrage family to a dinner where he had them beheaded, in this room. (Washington Irving, among others, didn't believe the legend - he offers a different explanation in his Tales of the Alhambra.)

Mocárabe (pictorial explanation here, or more detailed explanation here) is the technique that creates the cloud-like formations in Islamic architecture (The formations are hard to photograph - their details tend to blur, like a trying to photograph the details of a cloud.) Mocárabe is said to be a symbolic representation of the cave where Mohammed received his revelation.

Below is a series of various photos I took in various places trying to describe in more detail what Mocárabe is. Can you imagine what it must have been like laboring at creating ceilings like that?

(How does one keep them free of dust and cobwebs? If I were a spider, I would think it to be heaven.)The Palace of Carlos V

King Carlos V was Lord of the Netherlands as titular Duke of Burgundy from 1506, King of Spain (Castile and Aragon) from 1516, and Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 until his death in 1558. His many titles had him travelling around Europe, among other things defending royalty, the Holy Roman Empire, and the Roman Catholic faith from the protestants and the reformation.

In 1526 he decided to have the Palace of Carlos V built inside the Alhambra for his occasional use. It was designed as a Renascence building, its plan is a circle inside of a square. The work went on past his death until work was finally abandoned in 1637, unfinished. In 1923 Leopoldo Torres Balbas, curator of the Alhambra at that time, devised a plan to finish it.

Partal

The Partal in the oldest palace in the Alhambra (dating from 1303-1309), but much of what you see in The Partal is more recent. The Casa de Partal was a private property until 1891. While in private ownership it underwent various changes.

The Grounds

After vising the palaces we wandered through the grounds, including the archaeological excavation of the Palace of the Abencerrages (Remember them, possibly headless, for whom the Hall of the Abencerrajes is named?).

|

| Pink = Tower of the Hall of the Abencerrajes, Tan/Gold = their palace, Green = its central pool. |

Mid-afternoon we wandered through the landscaped grounds, towards the bridge that connects Generalife to the Alhambra, stopping on our way at The Infants' Tower - The Tower of the Princesses.

The Tower of the Princesses

After wandering through the grounds toward the bridge to Generalife, let's pause at The Infants' Tower - The Tower of the Princesses and linger a bit with Washington Irving.

|

| Photo of the Ceiling of the Tower of the Princesses (The Infant's Tower) from the Alhambra's official website |

|

| The Tower of the Princesses prior to restoration from The Alhambra published by The Guteberg Project |

During his months in the Alhambra Washington Irving could have camped in the Tower of the Princesses. If so, perhaps that's how he became so intrigued by it and wrote his Tale of the Three Princesses. I can imagine that in relation to one of my own experiences.

One of my favorite memories was when I was bivouacking in a high-alpine meadow surrounded by glaciers during a multi-day hike/scramble. A buddy and I watched the alpenglow darken, turned off the hiss of our small gas stove, poured the last of our hot chocolate into cups of whisky, then used flashlights to wander to our sleeping bags. I folded my clothes to use as a pillow then got into my bag, squirming while trying to find a position that wasn't too uncomfortable on the hard lumpy ground. Then we lay back and gazed upwards, letting our thoughts roam amidst the crowded starscape. Awareness slowly dimmed to black until in the pre-dawn morning the sky started to glow. I remember the chill when I got up nude, wandered nearby to piss, and stood there, watching the sun rise from beyond a nearby ridge.

I wonder how Washington Irving and Mateo Ximenes visited. Did they sleep inside the buildings of the Alhambra or outside, or in a guest house nearby? Did they cook over campfires and light their way with oil lanterns, or dine with the caretakers, or eat with the strange denizens of the Alhambra whom he describes? Did they sleep on the ground or on cots or in beds?

I can imagine Washington Irving laying there, gazing up at the ceiling of the Tower of Infants as the daylight dimmed to black, then in the morning wandering over to the window, watching the sun rise, and imagining his Tale of the Three Princesses.

Generalife

A bridge over the Cuesta del Rey Chico connects the Alhambra with the Generalilfe.

Generalife served many functions.

Water was foundational to the the Alhambra not only for its necessity for life in a hot arid climate, but also it was central to the culture and spirituality of Islam.

Generalife was the hub of the water system for water from the sultan's canal, the Acequia Real, which brought water from a dam on the Darro River six kilometers upstream. From its termination in Generalife the water was distributed to the Alhambra and the gardens and farms of Generalife.

Generalife was a source of food the Alhambra, with orchards and farms.

And Generalife served as a cool summer place with cool pleasant gardens and pools and the Generalife Palace.

We wandered through the gardens and the palace

|

| Over looking some of Generalife's orchards. The Alhamra is in the background across the ravine |

|

| Court of the main canal |

Cuesta del Rey Chico - The Slope of the Boy King

Most of the guidebooks give short shrift to the "backdoor way" to get to and from the Alhambra. But it was our favorite route (it's much easier when going downhill - to some people, parts of it may seem steep, though not to people who walk a lot) - Cuesta del Rey Chico - The Slope of the Boy King (also known as 'Cuesta de los Chinos').

Between Generalife and the Alhambra there is a ravine with a broad path that runs down to the Darro River, terminating near the Paseo de los Tristes (The Path of the Grieving.) It is so named because during the middle ages it was the route of funeral processions to the graveyards above the Alhambra. Some would pay their last respects and turn back at the plaza rather than trudge to the top of the hill.

|

| Aerial view from Google Earth, annotations by me |

Our last view of the Tower of the Three Princesses:

The Aljibillo Bridge at the base of the Cuesta del Rey Chico crosses the Darro River to reach the plaza Paseo de los Tristes where its time to stop for dinner (early for Spaniards, late for us).

More of the Past

Before we leave Granada I must mention the The Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology of Granada in the Casa de Castril just 130 meters (~426 feet) from the Paseo de los Tristes down the Carrera del Darro towards the Plaza Nueva..

It has a collection of artifacts on display that encompasses the history of the area around Granada from prehistory and the Bronze Age;

through the gradual development of various primitive cultures;

through establishment of trade and settlements by the Phoenicians, Greeks, and Punics;

through when the Iberians of this area, the Bastetanians, for a time resisted the Roman invasion;

through the era of Roman colonization;

followed by the era of the Visigoths;

and the Islamic era;

into the Christian era.

One of the best things about the museum is its many explanatory signs concisely describing the history, accompanied by easily comprehended timelines.

|

| A segment of a mosaic tile floor found in a Roman villa in Granada |

The Future of the Past

Any large complex requires lots of continual work to avoid falling into disrepair.

It's even more difficult when the work is in part restorative and archaeological and requires special expertise.

All of that requires a continual source of funds. Throughout the world, monuments such as The Alhambra depend on the wealth and willingness of governments and patrons, and equally importantly, the tourist industry. The financial and tourism impacts of the current COVID-19 crisis presents a troubling threat to the world's heritage..

Escape from the Past

We spent all of our time in Granada in historic areas, but most of Granada is a modern city.

Granada has a reputation for wild nightlife (reportedly one of the best in Andalusia) lasting until after dawn. It is driven in part by the tourists, but especially by the 80,000 students at the University of Granada. See here, and here, and (especially if student age) here.

We were totally wiped each day from our walking, and at our age, didn't care about the nightlife. We didn't even get to the Botellodromo to mingle and pre-drink before going out for a late night/early morning of serious fun. But if younger, and especially if still single ..... well, .....

We left Granada heading to Ronda. Renfe was not yet done with their new very high-speed rail line to Granada. so they provided a bus to the modern station at the rail hub of Antequera-Santa Ana where we transferred to a train for the remainder of our trip to Ronda..

|

| From the bus we could see the new high-speed rail line running through olive groves |

The next stop on our journey, Ronda - 3 nights, two and a half days - will be less concerned with history and more purely physical fun, especially our bike trip. So it should be easier and faster for me to write the next part of this blog.

To return to Part 1 - Overview of the Trip, click here.

Up next: Ronda and Biking the Via Verde de la Sierra: click here.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.